Francois..

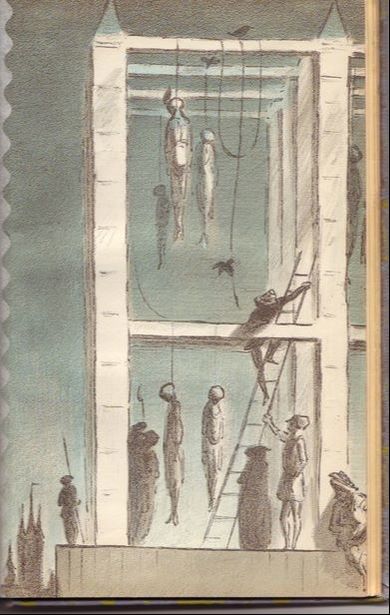

Mount Faucon Gallows (illustration Edward Ardizzone).

Mount Faucon Gallows (illustration Edward Ardizzone).

This page, François Villon, The People's Poet, which I will periodically change, features moments and/or scenes from this screenplay, or from the play Bobby at the Hanging of François Villon. Below are some of the moments from the first scenes of the play.

BOBBY AT THE HANGING OF FRANÇOIS VILLON

There are STAGES AT BOTH SIDES OF THE MAIN STAGE. ALL OF THE CHARACTERS THAT WILL APPEAR, except BOBBY, who is inspired by BOB DYLAN, but his full name is never spoken (and his lyrics only paraphrased), ARE FROM FIFTEENTH CENTURY PARIS, FRANCE.

ALL OF THE ACTORS, except BOBBY and FRANÇOIS are DRESSERS -- that is actors that either ‘dress’ the stage with items that suggest setting; help other Dressers transform into various characters, and/or transform themselves into various characters.

MANY ACTORS will play several roles -- which roles ultimately to be decided by the Director.

LIGHTS UP ON SIDE STAGE RIGHT, BOBBY in a basic hotel room with a few flourishes, early 1960s. MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT. A few lamps are lit, perhaps a candle or two that BOBBY lights for atmosphere.

BOBBY bears an uncanny resemblance to a young Bob Dylan, about 20, woolly-headed, thin, short. He sits at a typewriter, pounds keys in a bit of a tantrum. Dislikes what he’s written. Rips out the page, tears it up; scatters it like snow.

Next to an open suitcase, with clothes in disarray, is an unopened suitcase that he opens and turns over above the bed. ALL MANNER OF BOOKS spill on top of and around the bed. He picks up one; then another.

BOBBY

(reads the name of the nineteenth-century poet whose poems are in one of them)

Monsieur Paul Verlaine. No. You’re a bit too pretty for how I’m feelin tonight.

(reads the poet’s name on the other book)

Arthur Rimbaud.

(thumbs through to a poem)

“A Season in Hell.”

(throws the book down;

paraphrases a Dylan lyric)

It’s not Hell yet, but I’m getting there.

(seizes an old book, reads)

THE POEMS OF FRANÇOIS VILLON, translator H.B. McCaskie, London, 1946. Why the hell did ‘e give me this one? Five hundred years ago. Half a millennium. Don’t wanna go back more than two centuries.

He thumbs through the Villon book, stops and chuckles at some of the artsy black and white and faded tints that illustrate the poems. He stops at an illustration at the end of the book. He reads under the illustration.

BOBBY (cont’d)

Illustration of a poem he wrote after he was sentenced to hang on Montfaucon Gallows, Paris. Nice picture of corpses, and ravens waiting to eat them.

(reads in awkward French)

L’Epitache Villon: Freres humain qui après nous vivez.

(reads the English translation on the opposite side of the page)

Fellow humans that after us remain

Don’t be harder on us than what’s our due

For if you show some pity for our pain

The sooner God’ll show mercy to you

(flips to the preface; bursts into laughter at what he reads)

Born 1431. Died nobody knows when. Hey, François, maybe you’re still alive?

(reads more)

Hmmm. Last name ‘de Montcorbier’? When did you change it, and why? I changed my last name too. I like Villon, but not François. Half the men in France must be François’s.

BOBBY clears the bed of all the books, crashes, exhausted onto it. The Villon book pressed to his chest, he falls into a deep sleep.

LIGHTS UP ON THE MAIN STAGE. AFTERNOON, SPRING, 1456, MONTFAUCON GALLOWS. FRANÇOIS VILLON, 25, scruffy, but his infectious smile and fiery eyes make him attractive, stands ON A PLATFORM. His hands are bound behind him, a rope that hangs from a crossbeam above is around his neck.

Down a ways is another noose that awaits its victim. CHEERS AND BOOS are heard. FRANÇOIS cries out a variation of the poem that BOBBY read from the book of his poems.

FRANÇOIS

Men, brother men, brother men, sisters too

My body soon black ‘n no eyes

Pecked out by crows ‘n magpies

Pity me, pity, pity, pity, don’t boo

So God ‘ll pity you

APPLAUSE drowns out the BOOS. FRANÇOIS does his best to deliver a bow.

BOBBY shakes off his slumber, rises; looks over at FRANÇOIS.

BOBBY

So that’s how you die, eh, François?

FRANÇOIS shakes his head rapidly, as if trying to rid himself of a voice that he thinks is in his head.

BOBBY (cont’d)

I’m feelin what you’re feelin. Shall I hang myself and feel even more like you?

FRANÇOIS

(mutters)

Voices in my head? Have I lost my mind?

BOBBY

You hear me, François?

FRANÇOIS

Who’s talkin to me?

BOBBY flips through the Villon book, hits on a poem; reads the title.

BOBBY

“Debate Between the Heart and Body of François Villon.”

(reads the first lines)

It’s your heart, and see,

One slender thread is all I’m hanging by.

FRANÇOIS is stunned.

BOBBY

Come here. Come to me.

FRANÇOIS

I’m indisposed.

BOBBY

It’s like you’re in my dream and I’m, like, in yours. So dream yourself over here. C’mon. You’re in a dream. You can do whatever you dream.

FRANÇOIS attempts what BOBBY suggests. He wills the bonds to fall off his hands; takes the rope off his neck. No one puts it back around his neck.

As he enters BOBBY’S HOTEL ROOM, it’s as if his body is still on the gallows.

IN THE HOTEL ROOM, where LIGHTS COME UP A BIT, AND THOSE ON THE MAIN STAGE GO DOWN A BIT, FRANÇOIS looks around, totally mystified.

BOBBY (cont’d)

So, take a seat. I’m Bobby. I know who you are, François.

He produces a chair. FRANÇOIS doesn’t sit; looks around, amazed, terrified.

FRANÇOIS

Have I died? Is this Hell?

BOBBY

(bursts into laughter)

Could be! But those in charge seem to think it’s Heaven.

FRANÇOIS

Me in Heaven? Not possible. Who’s in charge?

BOBBY

Actually, I am. King of the Room. My famous friend insisted they give me a room at the inn.

FRANÇOIS

Famous friend?

BOBBY

They wanted to throw me out ‘cause I look kind’a funky. She demanded a room for me that one day’s gonna be America’s greatest songwriter, or she’ll sing ‘cross the wide world somethin ‘funky’ ‘bout them. Good thing, François, you speak English.

FRANÇOIS

English? I would never speak a word of the tongue of those goddamns that burned my Jeanne d’Arc to ashes. ‘Cept her heart! It refused to burn! I was born the very day she rose to Heaven, where they no doubt opened the doors wide for her. Only they’ve slammed the doors here. Forbidden to even say her name.

BOBBY

She is now the patron saint of France!

FRANÇOIS

Not possible. Where are you from anyway? What country? England?

BOBBY

America. Yeah, that’s right. America wasn’t discovered yet when you walked the earth.

FRANÇOIS

What year are you?

BOBBY

Five hundred years after your time, give or take a decade.

FRANÇOIS

Human beings still on earth in five hundred years? I figured they’d all die of the plague by then.

BOBBY

No more plagues. Wiped out. You lived in a whole other lifetime, when darkness was a virtue. Of course this century’s been pretty dark. There was two world wars.

FRANÇOIS

World wars?

BOBBY

Just about all of the countries on earth fightin each other. Oh, the world is round, not flat, and there’s millions and millions of people, more than you guys ever dreamed there’d be.

FRANÇOIS

The world wars didn’t kill everybody?

BOBBY

No, but World War III will. If it comes. No. When it comes. I dreamed, like I’m dreamin now, but not of the past, of the future. I was the only one left on earth. When I told my story to a psychiatrist he said he was havin the same dream, only he was the only one left on earth, so we agreed to be in each other’s dreams, so as not to be alone, you dig?

FRANÇOIS

What I see is that I don’t want you and me in the same dream. Before I go back to the noose, just tell me, Future Man, how does my story end? Any deus ex machina waitin in the wings?

BOBBY

You know ‘bout deus ex machina’s?

FRANÇOIS

I read Aristotle. No bringin in gods on machines to save the day. Earn it! But such endings do happen in real life!

BOBBY

Nobody knows how and when you died, that’s what your bio says.

FRANÇOIS

There’s public record even of the thousands of poor schmucks hanged on Montfaucon, and I’m no poor schmuck. So maybe I don't hang?

(thumbs through the book)

Not hand-copied by monks?

BOBBY

Printin got invented.

FRANÇOIS

Oh, yeah, I heard somebody in Germany printed 200 Bibles.

BOBBY

Now millions of books in all subjects are printed all over the world everyday.

FRANÇOIS

How can I not get hanged? There’s Guardsmen everywhere. A lot hate me, want me dead. All the noble folk on the front rows, the Clergy behind them, and most’a the rabble down at the foot of the hill.

BOBBY

Many will love you in the future. Maybe me. Don’t worry about the boo’s. There’s some ‘boo’ in all of us.

(pats the book)

Don’t care to go back further than the nineteenth century. Verlaine and Rimbaud are quite enough.

FRANÇOIS

Who?

BOBBY

(cites Rimbaud, "Night of Hell," in a SEASON IN HELL)

Arthur Rimbaud: I die of thirst, I suffocate, I cannot cry out. This is hell--eternal pain! See how the fires flare up! I’m roasted to a turn. Demon, charge on!

FRANÇOIS

No more about Hell, all right?

BOBBY AT THE HANGING OF FRANÇOIS VILLON

There are STAGES AT BOTH SIDES OF THE MAIN STAGE. ALL OF THE CHARACTERS THAT WILL APPEAR, except BOBBY, who is inspired by BOB DYLAN, but his full name is never spoken (and his lyrics only paraphrased), ARE FROM FIFTEENTH CENTURY PARIS, FRANCE.

ALL OF THE ACTORS, except BOBBY and FRANÇOIS are DRESSERS -- that is actors that either ‘dress’ the stage with items that suggest setting; help other Dressers transform into various characters, and/or transform themselves into various characters.

MANY ACTORS will play several roles -- which roles ultimately to be decided by the Director.

LIGHTS UP ON SIDE STAGE RIGHT, BOBBY in a basic hotel room with a few flourishes, early 1960s. MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT. A few lamps are lit, perhaps a candle or two that BOBBY lights for atmosphere.

BOBBY bears an uncanny resemblance to a young Bob Dylan, about 20, woolly-headed, thin, short. He sits at a typewriter, pounds keys in a bit of a tantrum. Dislikes what he’s written. Rips out the page, tears it up; scatters it like snow.

Next to an open suitcase, with clothes in disarray, is an unopened suitcase that he opens and turns over above the bed. ALL MANNER OF BOOKS spill on top of and around the bed. He picks up one; then another.

BOBBY

(reads the name of the nineteenth-century poet whose poems are in one of them)

Monsieur Paul Verlaine. No. You’re a bit too pretty for how I’m feelin tonight.

(reads the poet’s name on the other book)

Arthur Rimbaud.

(thumbs through to a poem)

“A Season in Hell.”

(throws the book down;

paraphrases a Dylan lyric)

It’s not Hell yet, but I’m getting there.

(seizes an old book, reads)

THE POEMS OF FRANÇOIS VILLON, translator H.B. McCaskie, London, 1946. Why the hell did ‘e give me this one? Five hundred years ago. Half a millennium. Don’t wanna go back more than two centuries.

He thumbs through the Villon book, stops and chuckles at some of the artsy black and white and faded tints that illustrate the poems. He stops at an illustration at the end of the book. He reads under the illustration.

BOBBY (cont’d)

Illustration of a poem he wrote after he was sentenced to hang on Montfaucon Gallows, Paris. Nice picture of corpses, and ravens waiting to eat them.

(reads in awkward French)

L’Epitache Villon: Freres humain qui après nous vivez.

(reads the English translation on the opposite side of the page)

Fellow humans that after us remain

Don’t be harder on us than what’s our due

For if you show some pity for our pain

The sooner God’ll show mercy to you

(flips to the preface; bursts into laughter at what he reads)

Born 1431. Died nobody knows when. Hey, François, maybe you’re still alive?

(reads more)

Hmmm. Last name ‘de Montcorbier’? When did you change it, and why? I changed my last name too. I like Villon, but not François. Half the men in France must be François’s.

BOBBY clears the bed of all the books, crashes, exhausted onto it. The Villon book pressed to his chest, he falls into a deep sleep.

LIGHTS UP ON THE MAIN STAGE. AFTERNOON, SPRING, 1456, MONTFAUCON GALLOWS. FRANÇOIS VILLON, 25, scruffy, but his infectious smile and fiery eyes make him attractive, stands ON A PLATFORM. His hands are bound behind him, a rope that hangs from a crossbeam above is around his neck.

Down a ways is another noose that awaits its victim. CHEERS AND BOOS are heard. FRANÇOIS cries out a variation of the poem that BOBBY read from the book of his poems.

FRANÇOIS

Men, brother men, brother men, sisters too

My body soon black ‘n no eyes

Pecked out by crows ‘n magpies

Pity me, pity, pity, pity, don’t boo

So God ‘ll pity you

APPLAUSE drowns out the BOOS. FRANÇOIS does his best to deliver a bow.

BOBBY shakes off his slumber, rises; looks over at FRANÇOIS.

BOBBY

So that’s how you die, eh, François?

FRANÇOIS shakes his head rapidly, as if trying to rid himself of a voice that he thinks is in his head.

BOBBY (cont’d)

I’m feelin what you’re feelin. Shall I hang myself and feel even more like you?

FRANÇOIS

(mutters)

Voices in my head? Have I lost my mind?

BOBBY

You hear me, François?

FRANÇOIS

Who’s talkin to me?

BOBBY flips through the Villon book, hits on a poem; reads the title.

BOBBY

“Debate Between the Heart and Body of François Villon.”

(reads the first lines)

It’s your heart, and see,

One slender thread is all I’m hanging by.

FRANÇOIS is stunned.

BOBBY

Come here. Come to me.

FRANÇOIS

I’m indisposed.

BOBBY

It’s like you’re in my dream and I’m, like, in yours. So dream yourself over here. C’mon. You’re in a dream. You can do whatever you dream.

FRANÇOIS attempts what BOBBY suggests. He wills the bonds to fall off his hands; takes the rope off his neck. No one puts it back around his neck.

As he enters BOBBY’S HOTEL ROOM, it’s as if his body is still on the gallows.

IN THE HOTEL ROOM, where LIGHTS COME UP A BIT, AND THOSE ON THE MAIN STAGE GO DOWN A BIT, FRANÇOIS looks around, totally mystified.

BOBBY (cont’d)

So, take a seat. I’m Bobby. I know who you are, François.

He produces a chair. FRANÇOIS doesn’t sit; looks around, amazed, terrified.

FRANÇOIS

Have I died? Is this Hell?

BOBBY

(bursts into laughter)

Could be! But those in charge seem to think it’s Heaven.

FRANÇOIS

Me in Heaven? Not possible. Who’s in charge?

BOBBY

Actually, I am. King of the Room. My famous friend insisted they give me a room at the inn.

FRANÇOIS

Famous friend?

BOBBY

They wanted to throw me out ‘cause I look kind’a funky. She demanded a room for me that one day’s gonna be America’s greatest songwriter, or she’ll sing ‘cross the wide world somethin ‘funky’ ‘bout them. Good thing, François, you speak English.

FRANÇOIS

English? I would never speak a word of the tongue of those goddamns that burned my Jeanne d’Arc to ashes. ‘Cept her heart! It refused to burn! I was born the very day she rose to Heaven, where they no doubt opened the doors wide for her. Only they’ve slammed the doors here. Forbidden to even say her name.

BOBBY

She is now the patron saint of France!

FRANÇOIS

Not possible. Where are you from anyway? What country? England?

BOBBY

America. Yeah, that’s right. America wasn’t discovered yet when you walked the earth.

FRANÇOIS

What year are you?

BOBBY

Five hundred years after your time, give or take a decade.

FRANÇOIS

Human beings still on earth in five hundred years? I figured they’d all die of the plague by then.

BOBBY

No more plagues. Wiped out. You lived in a whole other lifetime, when darkness was a virtue. Of course this century’s been pretty dark. There was two world wars.

FRANÇOIS

World wars?

BOBBY

Just about all of the countries on earth fightin each other. Oh, the world is round, not flat, and there’s millions and millions of people, more than you guys ever dreamed there’d be.

FRANÇOIS

The world wars didn’t kill everybody?

BOBBY

No, but World War III will. If it comes. No. When it comes. I dreamed, like I’m dreamin now, but not of the past, of the future. I was the only one left on earth. When I told my story to a psychiatrist he said he was havin the same dream, only he was the only one left on earth, so we agreed to be in each other’s dreams, so as not to be alone, you dig?

FRANÇOIS

What I see is that I don’t want you and me in the same dream. Before I go back to the noose, just tell me, Future Man, how does my story end? Any deus ex machina waitin in the wings?

BOBBY

You know ‘bout deus ex machina’s?

FRANÇOIS

I read Aristotle. No bringin in gods on machines to save the day. Earn it! But such endings do happen in real life!

BOBBY

Nobody knows how and when you died, that’s what your bio says.

FRANÇOIS

There’s public record even of the thousands of poor schmucks hanged on Montfaucon, and I’m no poor schmuck. So maybe I don't hang?

(thumbs through the book)

Not hand-copied by monks?

BOBBY

Printin got invented.

FRANÇOIS

Oh, yeah, I heard somebody in Germany printed 200 Bibles.

BOBBY

Now millions of books in all subjects are printed all over the world everyday.

FRANÇOIS

How can I not get hanged? There’s Guardsmen everywhere. A lot hate me, want me dead. All the noble folk on the front rows, the Clergy behind them, and most’a the rabble down at the foot of the hill.

BOBBY

Many will love you in the future. Maybe me. Don’t worry about the boo’s. There’s some ‘boo’ in all of us.

(pats the book)

Don’t care to go back further than the nineteenth century. Verlaine and Rimbaud are quite enough.

FRANÇOIS

Who?

BOBBY

(cites Rimbaud, "Night of Hell," in a SEASON IN HELL)

Arthur Rimbaud: I die of thirst, I suffocate, I cannot cry out. This is hell--eternal pain! See how the fires flare up! I’m roasted to a turn. Demon, charge on!

FRANÇOIS

No more about Hell, all right?